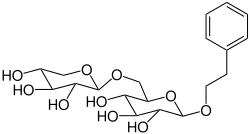

Phenethylprimverosid

Phenethylprimverosid ist ein natürlich vorkommendes Glycosid aus β-D-Primverose und dem Aglycon 2-Phenylethanol.

| Strukturformel | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| Allgemeines | |||||||||||||

| Name | Phenethylprimverosid | ||||||||||||

| Summenformel | C19H28O10 | ||||||||||||

| Externe Identifikatoren/Datenbanken | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Eigenschaften | |||||||||||||

| Molare Masse | 416,4 g·mol−1 | ||||||||||||

| Sicherheitshinweise | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Soweit möglich und gebräuchlich, werden SI-Einheiten verwendet. Wenn nicht anders vermerkt, gelten die angegebenen Daten bei Standardbedingungen (0 °C, 1000 hPa). | |||||||||||||

Vorkommen

BearbeitenPhenethylprimverosid ist neben Benzylprimverosid, Linalylprimverosid, Geranylprimverosid und (Z)-3-Hexenolprimverosid Bestandteil des Aromas von Tee.[2][3][4][5][6][7] Daneben kommt es auch in Pomelo[8], der Sauerkirsche[9], Ingwer[10], Rosa damascena[11], Olivenbäumen (v. a. den Blättern)[12][13], dem Hundsgiftgewächs Apocynum venetum[14], Alangium platanifolium aus der Gattung Alangium[15], Callianthemum taipaicum aus der Gattung der Schmuckblumen[16] und in Gomphrena celoisiodes[17] vor.

-

Teepflanze

-

Pomelo

-

Ingwer

-

Rosa damascena

-

Olivenbaum

-

Apocynum venetum

Biosynthese

BearbeitenDie Biosynthese in Teepflanzen wurde untersucht. Dabei findet eine zweistufige Glycosylierung statt, zuerst mit Glucose, dann mit Xylose. Eine Glycosyltransferase bildet Glucoside von verschiedenen Alkoholen (neben 2-Phenylethanol auch (Z)-3-Hexenol, Linalool und Benzylalkohol). Eine zweite kann dann spezifisch diese Glucoside durch Übertragung von Xylose in Primveroside überführen.[5] Ebenso wurde die Biosynthese in Olivenbäumen untersucht, wo biosynthetische Vorläufer Phenethylamin und 2-Phenylethanol sind.[13]

Eigenschaften

BearbeitenPhenethylprimverosid inhibiert die C30-Endopeptidase von SARS-CoV-2.[10]

Synthese

BearbeitenMittels Umglycosylierung des Primverosids von p-Nitrophenol mittels Penicillium multicolor können diverse andere Primveroside, darunter auch Phenethylprimverosid im Millimol-Maßstab hergestellt werden.[18]

Einzelnachweise

Bearbeiten- ↑ Dieser Stoff wurde in Bezug auf seine Gefährlichkeit entweder noch nicht eingestuft oder eine verlässliche und zitierfähige Quelle hierzu wurde noch nicht gefunden.

- ↑ Dongmei Wang, Eriko Kurasawa, Yuichi Yamaguchi, Kikue Kubota, Akio Kobayashi: Analysis of Glycosidically Bound Aroma Precursors in Tea Leaves. 2. Changes in Glycoside Contents and Glycosidase Activities in Tea Leaves during the Black Tea Manufacturing Process. In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. Band 49, Nr. 4, 1. April 2001, S. 1900–1903, doi:10.1021/jf001077+.

- ↑ Wenfei Guo, Ryuji Hosoi, Kanzo Sakata, Naoharu Watanabe, Akihito Yagi, Kazuo Ina, Shaojun Luo: ( S )-Linalyl, 2-Phenylethyl, and Benzyl Disaccharide Glycosides Isolated as Aroma Precursors from Oolong Tea Leaves. In: Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. Band 58, Nr. 8, Januar 1994, S. 1532–1534, doi:10.1271/bbb.58.1532.

- ↑ Dongmei Wang, Takako Yoshimura, Kikue Kubota, Akio Kobayashi: Analysis of Glycosidically Bound Aroma Precursors in Tea Leaves. 1. Qualitative and Quantitative Analyses of Glycosides with Aglycons as Aroma Compounds. In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. Band 48, Nr. 11, 1. November 2000, S. 5411–5418, doi:10.1021/jf000443m.

- ↑ a b Shoji Ohgami, Eiichiro Ono, Manabu Horikawa, Jun Murata, Koujirou Totsuka, Hiromi Toyonaga, Yukie Ohba, Hideo Dohra, Tatsuo Asai, Kenji Matsui, Masaharu Mizutani, Naoharu Watanabe, Toshiyuki Ohnishi: Volatile Glycosylation in Tea Plants: Sequential Glycosylations for the Biosynthesis of Aroma β -Primeverosides Are Catalyzed by Two Camellia sinensis Glycosyltransferases. In: Plant Physiology. Band 168, Nr. 2, Juni 2015, S. 464–477, doi:10.1104/pp.15.00403, PMID 25922059, PMC 4453793 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Masayuki Yoshikawa, Seikou Nakamura, Yasuyo Kato, Koudai Matsuhira, Hisashi Matsuda: Medicinal Flowers. XIV.1) New Acylated Oleanane-Type Triterpene Oligoglycosides with Antiallergic Activity from Flower Buds of Chinese Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis). In: Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. Band 55, Nr. 4, 2007, S. 598–605, doi:10.1248/cpb.55.598.

- ↑ Toshio Morikawa, Seikou Nakamura, Yasuyo Kato, Osamu Muraoka, Hisashi Matsuda, Masayuki Yoshikawa: Bioactive Saponins and Glycosides. XXVIII. New Triterpene Saponins, Foliatheasaponins I, II, III, IV, and V, from Tencha (the Leaves of Camellia sinensis). In: CHEMICAL & PHARMACEUTICAL BULLETIN. Band 55, Nr. 2, 2007, S. 293–298, doi:10.1248/cpb.55.293.

- ↑ Desen Su, Yunyun Zheng, Ziqiang Chen, Yuwu Chi: Simultaneous determination of six glycosidic aroma precursors in pomelo by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. In: The Analyst. Band 146, Nr. 5, 2021, S. 1698–1704, doi:10.1039/D0AN01705A.

- ↑ Wilfried Schwab, Gerhard Scheller, Peter Schreier: Glycosidically bound aroma components from sour cherry. In: Phytochemistry. Band 29, Nr. 2, 1990, S. 607–612, doi:10.1016/0031-9422(90)85126-Z.

- ↑ a b Laleh Babaeekhou, Maryam Ghane, Mahdi Abbas-Mohammadi: In silico targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and main protease by biochemical compounds. In: Biologia. Band 76, Nr. 11, November 2021, S. 3547–3565, doi:10.1007/s11756-021-00881-z, PMID 34565804, PMC 8456686 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Wenfei Guo, Ryuji Hosoi, Kanzo Sakata, Naoharu Watanabe, Akihito Yagi, Kazuo Ina, Shaojun Luo: ( S )-Linalyl, 2-Phenylethyl, and Benzyl Disaccharide Glycosides Isolated as Aroma Precursors from Oolong Tea Leaves. In: Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. Band 58, Nr. 8, Januar 1994, S. 1532–1534, doi:10.1271/bbb.58.1532.

- ↑ M.E. Alañón, M. Ivanović, A.M. Gómez-Caravaca, D. Arráez-Román, A. Segura-Carretero: Choline chloride derivative-based deep eutectic liquids as novel green alternative solvents for extraction of phenolic compounds from olive leaf. In: Arabian Journal of Chemistry. Band 13, Nr. 1, Januar 2020, S. 1685–1701, doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2018.01.003.

- ↑ a b Hiroshi Saimaru, Yutaka Orihara: Biosynthesis of acteoside in cultured cells of Olea europaea. In: Journal of Natural Medicines. Band 64, Nr. 2, April 2010, S. 139–145, doi:10.1007/s11418-009-0383-z.

- ↑ Toshiyuki Murakami, Akinobu Kishi, Hisashi Matsuda, Masao Hattori, Masayuki Yoshikawa: Medicinal Foodstuffs. XXIV. Chemical Constituents of the Processed Leaves of Apocynum venetum L.: Absolute Stereostructures of Apocynosides I and II. In: Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. Band 49, Nr. 7, 2001, S. 845–848, doi:10.1248/cpb.49.845.

- ↑ Hideaki Otsuka, Yasuyuki Takeda, Kazuo Yamasaki: Xyloglucosides of benzyl and phenethyl alcohols and Z-hex-3-en-1-ol from leaves of Alangium platanifolium var. trilobum. In: Phytochemistry. Band 29, Nr. 11, Januar 1990, S. 3681–3683, doi:10.1016/0031-9422(90)85306-Z.

- ↑ Dong-Mei Wang, Wen-Jun Pu, Yong-Hong Wang, Yu-Juan Zhang, Shan-Shan Wang: A New Isorhamnetin Glycoside and Other Phenolic Compounds from Callianthemum taipaicum. In: Molecules. Band 17, Nr. 4, 17. April 2012, S. 4595–4603, doi:10.3390/molecules17044595, PMID 22510608, PMC 6268643 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Do Thi Trang, Bui Huu Tai, Pham Hai Yen, Duong Thi Hai Yen, Nguyen Xuan Nhiem, Phan Van Kiem: Study on water soluble constituentsfrom Gomphrena celoisiodes. In: Vietnam Journal of Chemistry. Band 57, Nr. 2, April 2019, S. 229–233, doi:10.1002/vjch.201900011.

- ↑ Kazutaka Tsuruhami, Shigeharu Mori, Kanzo Sakata, Satoshi Amarume, Shigetaka Saruwatari, Takeomi Murata, Taichi Usui: Efficient Synthesis of β‐Primeverosides as Aroma Precursors by Transglycosylation of β‐Diglycosidase from Penicillium multicolor. In: Journal of Carbohydrate Chemistry. Band 24, Nr. 8-9, 1. November 2005, S. 849–863, doi:10.1080/07328300500439413.